Backlash

When women speak up, men shout louder

I heard this story a few years ago and it struck me then as revealing and typical.

This guy was at work, waiting for a lift. A woman was also waiting. The lift arrived and he said: ‘After you’, gesturing for her to go ahead. She said: ‘No, after you.’ A little stand-off ensued . It ended only when he went into the lift, said: ‘Fuck you’ and pressed the button before she could enter.

It came back to me again recently when I was reading about how young men seem to be diverging from young women in terms of their politics and attitudes. In many countries young men appear to be becoming more conservative and young women more progressive and liberal. It’s quite a sudden and very marked trend, as explained brilliantly by the data journalist John Burn-Murdoch in the Financial Times.

Burn-Murdoch says:

‘In the US, Gallup data shows that after decades where the sexes were each spread roughly equally across liberal and conservative world views, women aged 18 to 30 are now 30 percentage points more liberal than their male contemporaries. That gap took just six years to open up.’

It’s a very similar picture, he says, in Germany, Poland, the UK, South Korea, China, Tunisia. And what’s striking about the charts he produced is that the divergence between young men and women becomes really stark in the later 2010s. More specifically, women’s attitudes, which had generally been becoming more liberal, became markedly more so. And men’s either flatlined (in the UK) or went into sharp decline.

So the later 2010s? Mmm… what might have happened then to cause such a shift? Burn-Murdoch is clear:

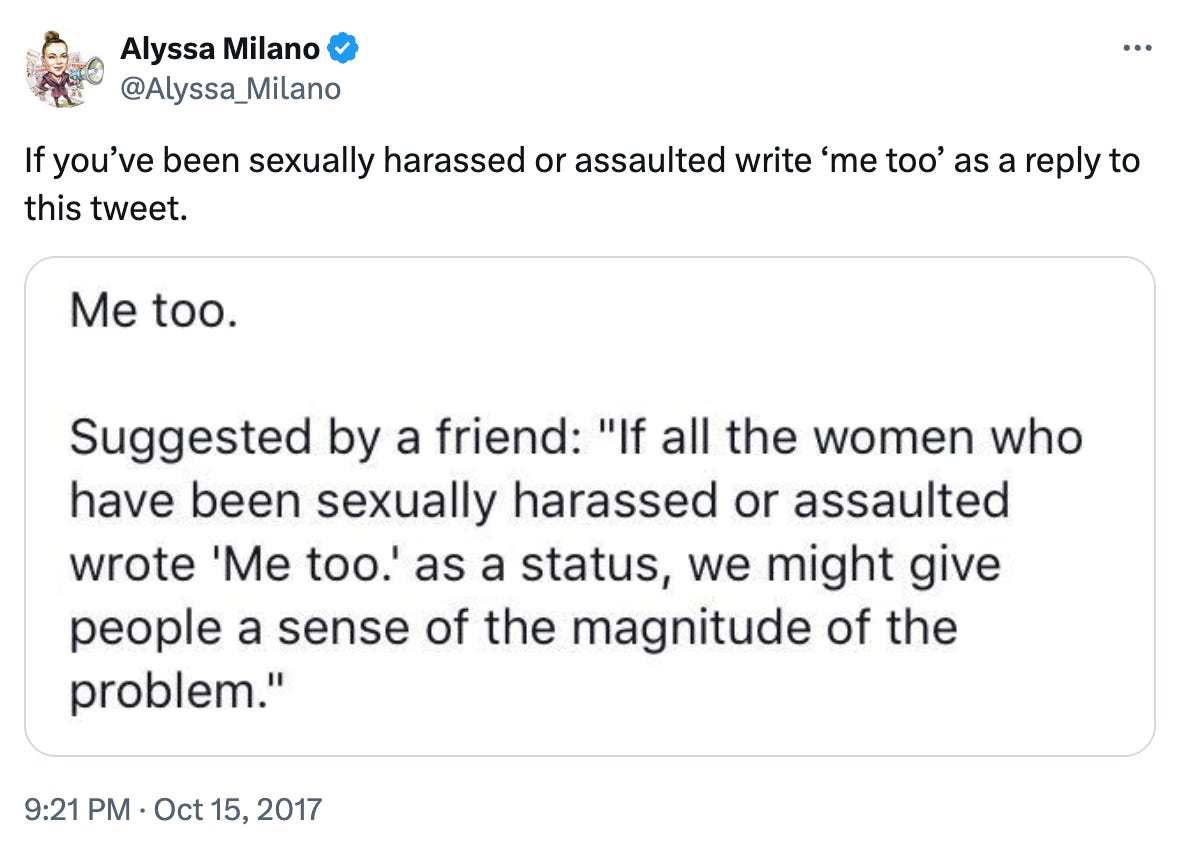

‘The #MeToo movement was the key trigger.’

That’s what I want to talk about. Not so much #MeToo, but the ‘backlash’. How some men have reacted to it and doubled down on their problematic relationship with and attitudes towards women. And that that’s what happens when women speak up. Men shout louder. Not all men, obviously.

Comeuppance

#MeToo was a huge story and moment in so many ways. For women, primarily. I think from the moment the 17-year-old me saw a guy on a packed Paris Metro standing less than a foot away from my then girlfriend who was grinningly, enthusiastically, just staring at her breasts (with me not saying a word), I think I realised that being a woman was different to being a man. The unwanted, unpleasant, uncomfortable attention that men could pay women, and so obviously enjoy paying them, and so obviously feel entitled to pay them, was something alien to me. I thought from then on that I have no idea what that would feel like.

To me #MeToo was like the unthinkable happening. It was like men being called out and then prosecuted for going to work, or talking about football. They were doing what they always did, something they didn’t even see as a problem, and suddenly it was completely unacceptable and police were being called and they were castigated and shamed and jailed.

For some men, it prompted some proper thinking and reckoning. Some will have thought: Yes, I’ve been like that. I did once, maybe more, act in a totally unacceptable way towards a woman or women and I can now see that that was wrong. Maybe they were affected by testimonies from the likes of Rose McGowan, about how big-shot Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein raped her when she was a 23-year-old actor. Or from the 80-plus other women who said Weinstein raped, assaulted or harassed them. All those encounters, every one of them, were consensual, said Weinstein, who was jailed for 23 years in 2020 and additionally for 16 years in 2023 on separate charges. The backlash can even be seen in that he is appealing against the 2020 conviction for a criminal sex act. Gotta fight back boys.

But is the power balance between women and men being permanently altered and made more even and equitable? I somehow doubt it, judging by stats like those published by Burn-Murdoch in the FT or a survey reported by The Guardian this month. This found that:

‘Boys and men from generation Z are more likely than older baby boomers to believe that feminism has done more harm than good.’

That made me think. So the seemingly inexorable progress from one generation to the next, how we, however slowly, become more socially liberal and less unthinkingly accepting of outdated prejudices and unfairnesses, has stopped when it comes to men’s attitudes to feminism. In fact we’ve gone backwards.

The poll The Guardian reported on was conducted by Ipsos for King’s College London’s Policy Institute and the Global Institute for Women’s Leadership. It found that:

‘On feminism, 16% of gen Z males felt it had done more harm than good. Among over-60s the figure was 13%.’

So there are more dodgy young blokes than dodgy old blokes now. Good grief.

‘This is a new and unusual generational pattern,’ said Professor Bobby Duffy, director of the Policy Institute. ‘Normally, it tends to be the case that younger generations are consistently more comfortable with emerging social norms, as they grew up with these as a natural part of their lives.’

It’s still the case that more young men think that feminism has done more good than harm than don’t. But, Duffy said:

‘There is a consistent minority of between one-fifth and one-third who hold the opposite view. This points to a real risk of fractious division among this coming generation.’

Terf war

There’s another arena in which the backlash seems to be happening – gender ideology. Not trans rights, which very few people seem to have a problem with, but gender ideology, which seems to be a very different thing.

Gender ideology seeks to make someone’s gender – their identity, the way they feel about themselves, the often horribly stereotypical view of manly men and girly girls – more important than biological sex. Gender activists, led by organisations such as Stonewall, want laws to be rewritten to reflect gender rather than sex; so, for example, someone born a man who identifies as a woman can ‘be’ a woman as far as law and society is concerned. That means among other things they can access spaces – toilets, refuges, hospital wards – that were thus far supposed to be reserved for women. In fact Stonewall hasn’t even waited for laws to be rewritten; many organisations it has lobbied have simply done away with single-sex spaces or provisions.

When women began to question this ideology – again, around 2017 – with groups such as Woman’s Place UK holding meetings to discuss how these ‘proposed’ changes might affect women, they were often subjected to intimidating groups of mainly men protesting outside their meetings and seeking to stop them taking place. Those mainly men would wear balaclavas, hold placards saying what should be done to TERFs [trans-exclusionary radical feminists, the gender activists’ label for gender-critical women; why not call them WRSRFs – women’s rights supporting radical feminists?], get in the faces of women attending the meetings, block access, bang on doors and windows to disrupt proceedings. Sex Matters has a long list of such behaviour.

These are all tactics you might expect to see, and might even condone, if something despicable, evil or certainly illegal was going on inside. But women meeting to talk about their rights, their fears, their desire to protect themselves from threats that they know will follow if essential safeguards around them are taken away? (Which is not to say that a trans woman accessing a women’s bathroom is doing so only to assault women; it is to say that men who wish to do harm to women, and there are sadly enough of them, don’t need to have their task made easier and this change to law and practice, allowing essentially self-ID of sex, would make that a whole lot easier.)

It's weird how women meeting to talk about their rights, and women questioning the basis of gender ideology, are so readily called ‘anti-trans’. From what I’ve read over a few years, most ‘gender-critical’ feminists – those who question or disagree with the fundamentals of gender ideology – are not anti-trans at all, in fact are so often very pro-trans. They are saying that women’s rights are a separate issue that in certain areas come into conflict with trans rights, if trans rights means the introduction of self-ID.

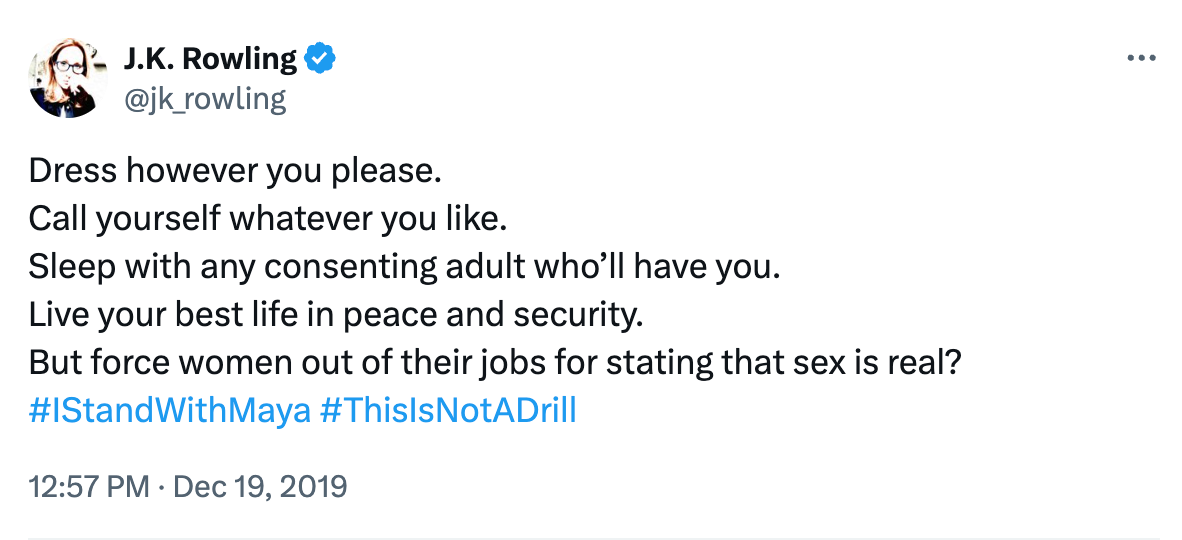

The extent to which some men have made efforts to shut down those debates among women and deliberately misrepresent what they are saying is quite telling when seen from the backlash perspective. This is particularly so when it comes to JK Rowling. She spoke up in the debate simply to say that women talking about their sex-based rights was valid.

She even went so far as to talk about the domestic violence she had experienced. So many women know that their female biology defines their existence, and largely because of the ways that our gendered society – and that means the one run by men – works. But for millions of Potterheads – and so many ‘progressives’ on the left, particulary men – she has dared to step out of the role dictated to her by society and by men – to be caring, to be supportive, to be not about her – and speak her mind and her truth. The abuse she suffered and still suffers is staggering.

Hadley Freeman wrote a brilliant column on men and gender ideology in The Sunday Times in January 2023. She has made me see so many things – particularly how women and Jews suffer the same kind of invisibility when it comes to ‘progressive’ types. The dudes who are so aware of rights being trampled on and discrimination being practised in so many other areas, simply do not see it when it comes to misogyny and antisemitism. Women and Jews are fair game it seems.

Freeman wrote:

‘Gender activism has become the permissible face of misogyny for a certain kind of allegedly progressive man. It gives him latitude to call women derogatory names and make spittle-flecked videos, insisting that anyone who has a problem with male-born people in women-only spaces is on the wrong side of history. The effect is men’s-rights activism, but the energy is very incel – shorthand for people who are “involuntarily celibate”. Incels rage online about women who selfishly refuse to have sex with them; gender activists rage against women who won’t just bloody well shut up about their concerns about safety and say what the men tell them to say.’

So what’s going on? Is it simply that a generation of young men are reacting to the emergence of a suddenly assertive and had-enough generation of young women? Those men feel they are under attack (a lot seem to really dislike the term ‘toxic masculinity’ according to that survey) and are not having it.

And the guy in the story about the lift (gen X rather than Z) was backlashing too. He is used to dictating what happens in interactions with women and now finds more women don’t want to go along with that.

To me, it’s a no-brainer; men oppress women in individual and systemic ways and we are still nowhere near understanding how to stop that. Yet we have to stop it. Maybe a lot of men think we already have; that the sexes are already more than equal enough; that we may even have gone ‘too far’. After all, as Caitlin Moran was telling us, it’s harder to be a young man these days than it is to be a young woman, apparently. Between me and them, there’s a serious discrepancy of views. So where’s the truth?

Back to the backlash

As always, I went looking for some articles or studies to back up my hunches. And this, by Constance Grady for Vox in February 2023, was the best, by far. She starts out by saying:

‘I started thinking about when the backlash to Me Too would arrive almost as soon as the Me Too movement took off in 2017. Most of the writers I know who cover feminism did the same. Not because we were pessimists, but because we knew: That’s just the way it goes.’

America, Grady says,

‘has never been willing to spend time caring about the safety of women without making them pay for it later. The Me Too moment was going to end. Then there was going to be a backlash, and it was going to hurt.

‘The backlash has arrived.’

Exhibit A in the backlash case is the overturning of Roe vs Wade. Since 1973, abortion had been legal across the United States. In June 2022, the US Supreme Court effectively took away the right for an American woman to decide on her pregnancy. Abortion is now banned outright in 14 states and severely restricted in seven others. It is hard to believe that decision was not at least in some part influenced by five years of MeToo, as well as four years of Donald Trump’s disgusting misogyny and his ability to load the Supreme Court with his favoured conservative judges (one of whom, you’ll remember, Brett Kavanaugh, vehemently denied that while at high school he sexually assaulted Christine Blasey Ford, a witness at his confirmation hearing that both Republican and Democratic senators said was ‘compelling’ and ‘credible’, according to Britannica). The irony.

Anyhoo, Grady quoted extensively from Susan Faludi’s 1991 book called, helpfully, Backlash: The Undeclared War Against American Women. Faludi was writing after Ronald Reagan’s conservative administration of the 1980s had provided a traditional and masculine antidote to the advances of the second-wave feminism of the 1970s. But she made clear she could have been writing about virtually any period in history.

Grady writes:

‘Importantly, the backlash is rarely the product of a grand conspiracy or concerted effort among sinister misogynists to bring women down. It’s simply a mass reaction to a mass movement. Those who enact the backlash, Faludi writes, are often unaware “of their role; some even consider themselves feminists. For the most part, its workings are encoded and internalized, diffuse and chameleonic.” But she finds the pattern of this diffuse, unplanned backlash emerging throughout American history, every time the women’s movement appears to be making gains.’

This is it. This is the point. ‘Every time the women’s movement appears to be making gains.’ Because too many men depend on women, need women, to do things for them, to prop them up, to do menial tasks for them. So if those women say no, they are not going to do that any more, then that man has a problem. Some might think OK, I’d better do that myself, or even, I might see if there’s anything I can do for the women in my life. But others see women only in this light and it’s then a her or me situation, a face-off, and then power structures and strength can be brought to bear.

I’ve said before how Richard V Reeves and Ian Leslie have written about the problems of ‘zero-sum’ thinking; where the assumption is that for one person or group to gain, another has to lose. This seems to be where some men’s rights activists or young male anti-feminists are.

Bethan Iley, a PhD student in social psychology at Queen's University Belfast, wrote on The Conversation about the role that Andrew Tate and Jordan Peterson have played on social media in fomenting the anti-feminist backlash.

‘It’s common for people like Tate and Peterson to justify their views by saying that men’s issues and concerns are routinely ignored. And it is indeed the case that male health, homelessness and suicide have been historically under-discussed and underfunded.

‘But to raise these issues as an argument against more freedom for women is to feed the false idea that men and women are battling for power.

‘This “us vs. them” perspective does emerge in political debate when one group feels threatened by another, generally when the other group is attaining power and resources. Such perceived competition may be further heightened if it is considered to be zero-sum – that is, when individuals believe that one group’s gain requires another group’s loss. Through this lens, women’s improving status in society must be hurting men’s opportunities. People who believe this may be motivated to reverse progress on gender equality. However, this notion is based on a false premise. Gender equality actually leads to more economic growth and so more jobs for everyone, regardless of gender.’

Constance Grady should have the last word on all this. She cautioned against making Weinstein out to be an ogre, an exception.

‘The question I keep asking myself during this time of backlash is: Are Weinstein’s convictions a victory, or are they a scapegoating?

‘I can’t shake the sense that these convictions are a way of targeting all the movement’s anger onto one man, rather than onto the systems that let him operate with impunity, or the other men who took advantage of those systems in perhaps slightly less grotesque ways than did Weinstein. Rather than doing the difficult work of redistributing power and thinking about what a meaningful response to various forms of sexual misconduct should look like, we can simply point to Weinstein’s fate and say, “See? We fixed it. And anyway, this predator isn’t as bad as Weinstein, so what does it matter?”

Absolutely. As appalling as Weinstein is, he is not really the problem. We all are, all of us men. And we need to fix it. The ‘difficult work’ is on us.