I’ve found another one! Another man worthy of ‘role model’ status, or at least one I find completely admirable and cool and want-to-be-like-him material. Woe Men started out as being more about bad men, and me damning them, which came very easily, but things are changing and I’m taking a slightly different view of masculinity, mine and others’.

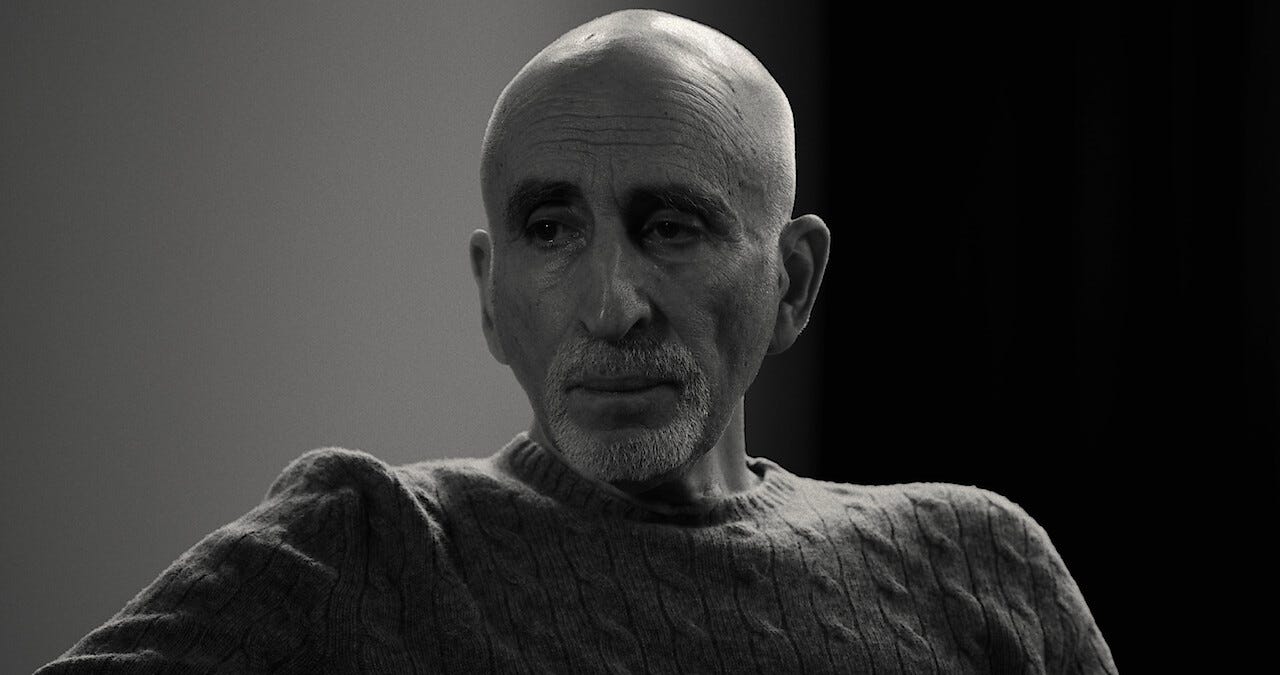

For now I want to talk about someone I mentioned a few posts ago (‘Congruence. That’s it’, from 12 January). I’d seen the film Stutz a while ago and found it (and him) completely amazing. The ‘him’ is Phil Stutz, the Los Angeles-based therapist who’s worked with many Hollywood stars, one of whom (Jonah Hill) made a Netflix documentary about him.

The film is about the genuinely warm relationship between this particular client and therapist; it’s about Hill wanting to honour ‘the life of somebody I deeply care about and respect’; and it’s about a therapist (unusually) becoming for a while at least the client and revealing quite a lot about himself and his personality. It’s that last bit that I found so fascinating. Therapists, by definition and certainly by training, know themselves better than most people and so have an ability to talk about themselves deeply and honestly and in a way that a lot of people can benefit from. It’s just they don’t do it very often. But when they do we should all listen.

Maybe it’s that honesty, combined with his humour and his sweariness, that made him so appealing to me. But I found Phil Stutz about as attractive as a man can be to me. Above his other qualities (warmth, compassion, intelligence) I think it’s to do with him being a man who has thought long and hard about life and has come to some conclusions about how to live it better: so for me the appealing men are not those who are really good at something or who have done something remarkable or succeeded against the odds. It’s those who grasp the day-to-day realities or even mundanities of life and know that they apply to them and to all of us. (For Stutz there are three aspects of reality ‘that no one gets to avoid’: pain, uncertainty and constant work. That might sound grim, but I love that.) And it’s dealing with those realities, rather than reaching some supposed ambition or pinnacle, that will bring us peace or contentment or whatever it is we’re searching for.

There’s something else about him too. I find myself identifying with him in ways I don’t completely understand. Some of them are obvious: he’s a therapist and I am about to resume studying to become one; he talks about his role as a focal point and centre of calm and sense in his family when growing up, and that chimes with me too; and then it turns out he’s had to fight against a notion, handed down to him, that men are bad and terrible, and yet he is one and how do you get over that? That’s me right now. So I feel a real connection with this person I’ve never met and have merely seen talk in a film and read being interviewed over a number of years.

Who is Phil Stutz?

Phil Stutz was born in New York in 1947. The defining moment of his childhood or even life happened when he was nine. His little brother Eddie, who had been diagnosed with a rare form of kidney cancer, died at the age of only three. Stutz vividly describes the moment he found out Eddie had died and how his parents just couldn’t deal with it or even talk about it.

‘… my parents collapsed. They couldn’t quite function as parents emotionally. They just couldn’t do it.’

Into the emotional family void it seems stepped the nine-year-old Phil Stutz, who seemed to be able to see or sense what was going on – or at least want to – in ways that his parents couldn’t.

‘His death became this giant weight that I had to carry around but nobody would admit the fucking weight was there.’

And he was so aware of a responsibility that seemed to rest on his young shoulders.

‘It was a fight against death and if I didn’t join the fight the whole family was going to fall apart.’

At that point in the film Jonah Hill says:

‘So, you became their therapist?’

Stutz replies:

‘That’s right. That’s exactly right.’

He became everyone else’s therapist too it seems.

‘Since I was a little kid people have always walked up to me and told me their problems. A little kid, I would be like 10 years old, a grown man would come up to me; most of them I didn’t even know and they would just pour their hearts out. Who knows where that comes from.’

A few years later Stutz and his father were visiting a friend in hospital and his father said to him:

‘I love you but if you don’t become a doctor I’ll never respect you.’

So he became a doctor. He went to medical school and chose psychiatry, working for a while with prisoners in New York’s notorious Rikers Island jail before setting himself up in private practice as a therapist.

His approach as a therapist

What sets Stutz apart from the vast majority of psychotherapists is his… impatience with the traditional methods. He explains his approach in the film:

‘The average shrink says don’t intrude on the patient’s process. They will come up with the answers when they’re ready. That sucks. That’s not acceptable.

‘When I got into psychiatry the model was I’m neutral. I’m just watching, I have no dog in this fight. It was a very slow process and there was a lot of suffering. You know me, my reaction would be: well then go fuck yourself. Are you kidding me?

‘If I’m dealing with someone with depression like that who’s afraid they won’t recover, I say: “Do what the fuck I tell you, do exactly what I tell you, I guarantee you will feel better. Guarantee, 100 per cent. It’s on me.”

‘I wanted speed in this. Not speed to cure somebody in a week, that’s impossible. But I wanted them to feel some change. Some forward motion. It gives them hope. It’s like, oh shit, that’s actually possible.’

The Tools

Stutz is known for his Hollywood clients and for his book The Tools: Transform Your Problems Into Courage, Confidence, and Creativity, published in 2012 and written with fellow therapist Barry Michels. As their website explains:

‘The Tools are quick practices that you can use in the moment to deal with the most common problems we all encounter.’

And as Jonah Hill says to Stutz at the outset of the film:

‘I want to present your tools and the teachings of you, Phil Stutz, my therapist, in a way that allows people to access them and use them to make their own life better.’

There are tools such as Inner Authority, The Mother and Active Love that are used to help with insecurity, while Reversal of Desire and The Tower can tackle deep-seated fears.

For Stutz,

‘a tool is a bridge between what you realise the problem is and the cause of the problem to over here actually gaining at least some control over the symptom.’

He gives an example of a typical client.

‘A guy’s depressed, he comes into my office and he says: I know my habits are shit, I know I’m undisciplined, I know I’m lazy, but if I only knew what I was supposed to be doing, what my mission was in life etc, I’d be like I was shot out of a gun.

‘But I don’t know what I’m supposed to be doing so I’m just going to be lazy and do nothing and from there obviously comes the depression.’

Stutz goes on to explain what he would try to do for such a client. It’s all to do with your life force.

‘The only way to find out what you should be doing and who you are is to activate your life force because your life force is the only part of you that’s actually capable of guiding you when you’re lost.’

There are three levels in the life force pyramid. The bottom layer is your relationship with your physical body. The middle layer is your relationship with other people. And the top layer is your relationship with yourself. At first you must concentrate on your body, by paying attention to exercise, diet and sleep.

Stutz then explains how relationships ‘are like pitons for rock climbers’, they can help you ‘get pulled back into life’.

‘The key to it is you have to take the initiative. If you’re waiting for them to take the initiative then you don’t understand this. You can invite somebody out to lunch that you don’t find interesting, it doesn’t matter. It will affect you anyway, in a positive way. That person represents the whole human race, symbolically.’

If my life force is lacking, this second layer feels like it holds the key for me. I feel as though I generally keep a distance between me and other people, I’m a bit off, and I’m not sure why. I fear perhaps that people will see the ‘real’ me, the insecure, not-very-good person who I try to hide. But as I get older it’s getting harder to hide that inner me. So it’s coming out and that’s difficult for me to handle.

Then at the top of this pyramid is your relationship with yourself. This is how Stutz describes this part in the film:

‘The best way to say this is to get yourself in a relationship with your unconscious because nobody knows what’s in their unconscious unless they activate it. And one trick of that is writing. It’s really a magical thing.

‘You enhance your relationship with yourself by writing. And someone might say write what? I’m not interested in anything. I’m not a writer. It doesn’t matter. If you start to write, the writing is like a mirror. It reflects what’s going on in your unconscious. And things will come out if you write like in a journal form that you didn’t know that you knew.

‘If you’re lost, don’t try to figure it out. Let it go and work on your life force first.

‘It’s about passion, increasing your life force so you can find out what you’re really passionate about. But step one is to be passionate about connecting to your own life force. And that, anybody can do that.

‘Everything else will fall into place.’

Someone else could say this and I’m not sure it would land quite as powerfully as it did for me when Stutz said it. It’s this appealing (to me) quality he has. He’s made a connection to me in lots of different ways and because of that his message sounds authentic. And experience and instinct tells me he’s right.

Wow, men!

The other bit that made me go ‘wow’ was when the tables were turned and Hill began asking Stutz questions. Hill’s mother appears in the film and joins Hill and Stutz in a conversation about her relationship with her son. Afterwards Hill asks Stutz about his own mother. She ‘was from a different planet,’ he says. Her father was a ‘psychopath’ who would beat up his wife and his mother’s younger sibling. But he ‘never touched my mother’. That, Stutz says,

‘was the worst torture for her of all. So I think, by the time she was eight, nine years old, she wouldn’t say a word to him.’

Then suddenly

‘he just ups and leaves. He doesn’t say anything, doesn’t tell them he’s leaving. In the middle of the night…’

As a result Stutz’s mother had a very negative view about men generally.

‘Every night at dinner, she’d give a tirade about men. “Men are this, men are that.” I couldn’t really disagree with her. My poor father had to be the cheerleader for this. He’d say: “Yeah, she’s right. Men are terrible.”

‘It didn’t occur to me until I was about 13, 14: “Shit, I’m a man. Hmm…”’

Hmm indeed. This thought didn’t really occur to me until I was well into my fifties, but it’s been a big thing for me. Imagine thinking that when you’re barely a teenage boy.

A bit later on, Hill asks Stutz

‘How do you think that affects you, having your mom hate men and you being a man?’

The tables are well and truly turned now. Stutz is on the couch, so to speak, and what he reveals about himself is perhaps a bit contrived (it is a film after all, made by his client and friend, and all kinds of factors go into the editing process) but nonetheless I found him genuine and as a result moving.

‘I can feel everybody waiting for the answer, but I don’t know if I know exactly the answer. I know one thing for sure. It made me insecure around women. I mean, that’s a no-brainer.

‘It was like there was no pathway inside me that could step to a woman and feel safe. I guess that’s the best way to say it.

‘… The way she [his mother] would make me feel is, “You have no right to even be doing this.” I overcame it a little bit, but not… I didn’t overcome it emotionally so much as I did just behaviourally.’

To all those people who just think that therapists have all the answers and must be completely sorted themselves, this is the perfect riposte. Stutz has been affected for a big part of his 70-odd years by the emotional impact his mother had on him. And he’s still trying to work it out.

‘I’ll tell you one thing, I’d be a much better partner now than I was years ago. Although that’s a very low bar.’

Hill keeps going with the therapist approach and then asks Stutz:

‘Did you ever override that wall that was built by your mom and get close in the way

you were scared to with a woman?’

What a question to ask a therapist.

‘I would say, yeah, once.’

Stutz says that ‘for various reasons’ he ‘can’t get into the specifics of it’ but does admit that this particular relationship ‘has been on and off for years’. He then cites his health issues (chronic fatigue syndrome and Parkinson’s) as one thing that affected the relationship and starts going off on a tangent about how his tremors haven’t been so bad that day and how Hill must be a help and would he mind following Stutz around a bit more often to keep the shakes at bay…

‘Don’t go on a fucking comedy routine right now. Stay on track, bro. I know what you’re doing.’

It’s touching and hilarious. The comedian and funny man trying to keep the serious therapist from dodging personal questions with humour and deflection. That’s very good.

And there’s men generally right there: trying to be emotionally honest and true yet finding it difficult and hiding behind the traditional mask of masculinity: bravado, humour, it’s nothing. But obviously Stutz knows it’s not nothing. And Hill does too. And slowly, gradually, a lot of us men are getting that same message too.

Links

• Dana Goodyear wrote a piece in The New Yorker back in 2011 about Stutz and his disciple Barry Michels and how they became the therapists to the stars in Hollywood.

‘The Jungians I’ve always been uncomfortable with, because they kind of drift,’ Stutz says. ‘They say that the dreams will tell you what to do, and that’s bullshit.’ Instead, he and Michels tell their patients what to do.’

• Actor John Cusack was a Stutz/Michels client and wrote a series of articles for HuffPost in 2012 that shed more light on their methods.

‘That was probably the thing that drew me to your method. You presented a set of operating principles, and you just said, “Go see if this stuff helps your life or not.” I don’t think we really spent much time rehashing the past.’

• Charles McNulty, the Los Angeles Times theatre critic, had a session with Stutz that was part interview, part therapy. It’s good.

‘Noticing that his energy was visibly drained after our intense hour together, I asked if there were any final thoughts he wanted to share before I left.

‘“No, actually,” he said, unable to resist a teaching moment. “Don’t be in that journalistic mode. Just be humble and do what I’m telling you. And remember, you’re an ignorant [blank]. And that more, more, more is less, less, less.”’

• Cheralyn Leeby, a therapist and academic from Florida, wrote a balanced review of Stutz the film on Psychology Today.

‘This multi-layered, transparent, novel, and loving healing process (done very carefully) might be the perfect prescription for the emotional and psychological aches that have become endemic to our society today.’

• Lucia Grosaru, a clinical psychologist, wrote a rather more scathing review on her Psychology Corner website. She calls Stutz ‘an abusive, unethical, narcissistic individual’.

‘Hill’s intentions regarding the film were pure and positive. He wanted to do something elegant, profound, and beautiful. I just feel that everything was hijacked by Stutz’s narcissism. If I got anything out of this documentary, it’s newfound respect for Hill.’

• Linda Marric, in The Jewish Chronicle, loved the film.

‘There are moments of frustration and moments of pure unadulterated joy running through Hill’s film, and one can’t help but cheer both patient and therapist, even if by the end we are no longer sure which is which. I have genuinely never felt the urge to recommend a film more.’